Print Blocks:

The "Print" blocks in the GraphLinq IDE serve the purpose of recording messages into the logs of a graph while it is running. These blocks play a crucial role in aiding experimentation, debugging, and event recording within the graph development process.

Main Use Cases:

Experimentation and Debugging: Using "Print" blocks to output values calculated by the graph is a valuable approach for experimenting with different blocks and testing the graph's functionality. During development, developers can quickly assess the behavior of the graph by logging intermediate results, variable values, and execution status. The real-time feedback provided by the "Print" blocks helps in identifying potential issues and streamlining the debugging process. As a local context is provided, it becomes easier to verify the correctness of the graph's logic.

Recording Graph Events: "Print" blocks also serve as a means to record significant events and activities within the graph. These messages are stored persistently in the logs associated with the specific graph. For instance, "Print" blocks can be utilized to record error messages when certain conditions go wrong, providing insights for error handling and troubleshooting. Moreover, they can be effectively used to monitor the frequency of user commands submitted to GraphLinq-based applications like Discord bots.

Examples:

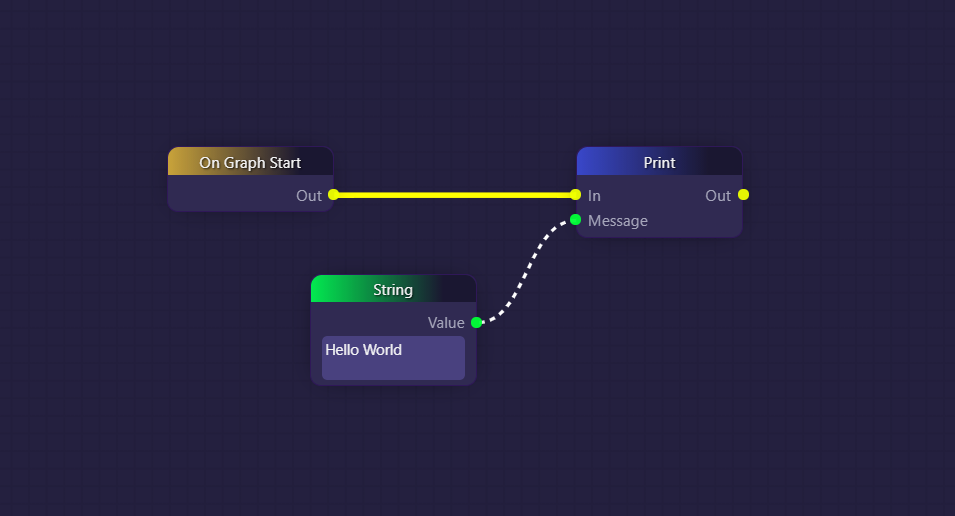

Simple "Hello World" Message: The simplest use of a "Print" block involves recording a message, such as "Hello World," into the logs at the beginning of the graph's execution. This helps in verifying that the graph has started successfully. The output message appears in the terminal at the bottom right of the IDE and is time-stamped for reference.

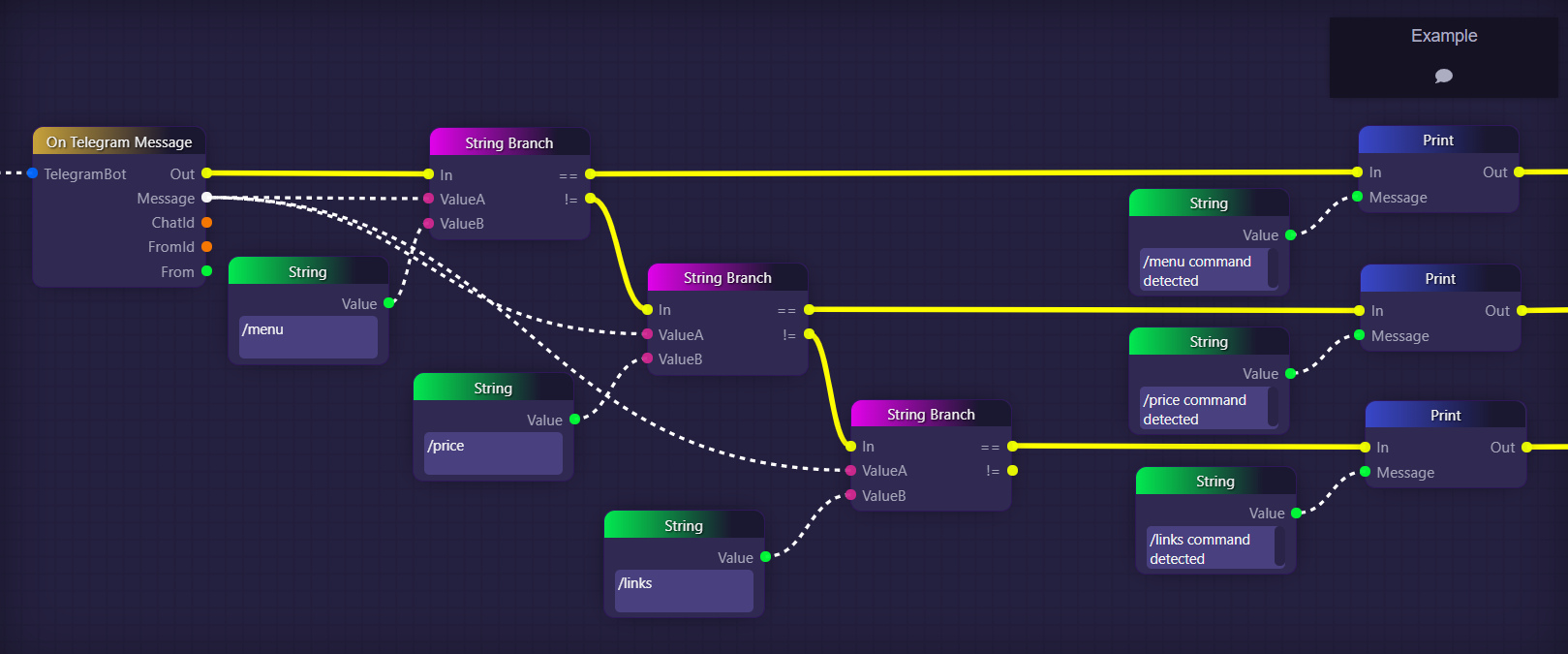

Recording Telegram Channel Commands: In a more complex scenario, "Print" blocks can be employed to record events when specific commands are detected in a Telegram channel. Using cascading "String Branch" blocks, messages submitted in the Telegram channel are checked to see if they match specific commands, such as "/menu", "/price", or "/links". Whenever these commands are detected, corresponding "Print" blocks are used to log messages in the graph's logs, indicating the commands' occurrences.

Note that the "Print" messages are not visible to the users in the Telegram channel; instead, they are stored in the graph's logs. This enables the graph owner to access and analyze the data later, determining the frequency and usage of different commands by members of the Telegram channel.

In conclusion, "Print" blocks are a powerful tool for developers to gain insights into their graph's behavior and operation. By providing real-time feedback and recording important events, these blocks contribute significantly to the efficient development, testing, and monitoring of graphs. The logs containing the "Print" messages offer valuable information for assessing the graph's performance and user interactions.

Here is the simplest possible use of a Print block, in which we are recording the string "Hello World" into the logs one time, upon the beginning of the graph's execution:

This would result in the following time-stamped message appearing in the terminal at the bottom right of the IDE:

![]()

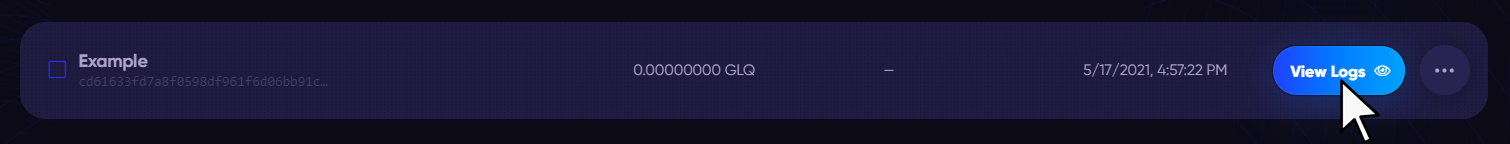

You can access the full logs for your graph by clicking on the "View Logs" button for your graph on the "My Graphs" page in the interface:

The following is a more involved example in which Print blocks are being used to record a note in the logs each time certain commands are detected in a Telegram channel:

In the above example, we are using cascading String Branch blocks in order to check every message submitted in a Telegram channel to see if it is one of three commands we are listening for "/menu", "/price", or "/links".

Presumably, if this was a real graph, then it would contain logic for each of these three commands that would cause our bot to react to the commands appropriately, for example by fetching the price of whatever token we care about and then outputting it into the Telegram channel whenever the "/price" command is detected. The implication here is that all such logic would appear to the right of our image, along those three yellow executive connections.

What we have done here is insert Print blocks into our three yellow branches to output messages into our logs that record which commands have been detected. These messages will not be seen by the users in the Telegram channel; rather, they will be stored in the graph's logs so that the owner of the graph could later access them and determine when and how frequently the different commands are used by members of the Telegram channel.

Last updated